Æthelflæd depicted in a window at Worcester Cathedral. (© B. Keeling)

This year marks the 1100th anniversary of the death of one of the most remarkable women in English history. Her name was Æthelflæd and she died at Tamworth in Staffordshire on 12th June 918. She was the eldest daughter of Alfred the Great, the most famous of all Anglo-Saxon kings. Alfred ruled the southern kingdom of Wessex, the land of the West Saxons, and it was there that Æthelflæd was born around the year 869.

King Alfred spent much of his reign fighting the heathen Viking armies that had raided and occupied large parts of what are now eastern and northern England. One of the lands that had suffered greatly was Mercia, formerly a large Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the midlands. At the time of Æthelflæd’s birth, much of Mercia had been overrun by the Great Heathen Army, a powerful force of mostly Danish Vikings that had arrived in Britain a few years earlier. During Æthelflæd’s childhood, the old line of Mercian monarchs ended and the kingdom collapsed under the Viking onslaught, with only a western portion remaining in English hands. By the early 880s, this last bastion of Mercian independence was ruled by a man called Æthelred. Although not generally described as a king, Æthelred wielded the same power as his royal predecessors and was determined to take back the lost territories. Contemporary chroniclers writing in the Old English language referred to him as myrcna hlaford, ‘The Lord of the Mercians’, and this may have been his preferred title.

Little is known of Æthelred’s origins but he appears to have emerged in south-west Mercia, a region that included the lower valley of the River Severn and the important ecclesiastical centres of Gloucester and Worcester. To the north and east lay other Mercian lands that had been devastated or occupied by Viking warbands. To the west lay the Welsh, the native Britons of Wales, guarding their own small kingdoms against Vikings and English alike. To the south lay Wessex, where King Alfred ruled.

Anglo-Saxon England in the late ninth century

Æthelred rose to power at a time when Alfred was making a bold stand against the Viking armies in the east. The two men pooled their military resources to mount joint campaigns, simultaneously forging a close political relationship in which Alfred became Æthelred’s overlord. This led to the Lord of the Mercians becoming a key figure at the West Saxon court as well as Alfred’s most important ally. Co-operation between Mercian and West Saxon forces probably lay behind Alfred’s recapture of London in 886, a victory that drove out a Viking warband and restored the city to English rule. Soon afterwards, Alfred sealed his friendship with Æthelred by giving him the hand of his daughter Æthelflæd in marriage.

Æthelred was considerably older than his bride. He had been involved in war and politics for some two decades and was a man of mature age. Æthelflæd was still a teenager, yet one who had known considerable hardship and peril. In the winter of early 878, when she was around eight or nine years old, she had barely escaped alive after Vikings launched a surprise attack on her father’s hall. With her parents and younger siblings she had then lived as a fugitive in the Somerset marshes for several months, barely surviving the cold and hunger. Such a traumatic experience no doubt left its mark on her character, hardening rather than weakening her spirit. At the time of her wedding to the Lord of the Mercians she probably appeared older and wiser than her years, a serious young woman who fully understood what was required of her as the wife of her father’s closest ally.

Viking warriors, from a French manuscript of c. 1100.

Through her mother, a native of Mercia, Æthelflæd could claim kinship with her husband’s subjects. It is clear that the Mercians quickly accepted her as one of their own, recognising her as a strong, charismatic individual in the mould of her mighty father. Æthelred, too, acknowledged her talents and gave her many opportunities to use them. Together, the couple set about the task of securing and strengthening their domain by establishing burhs (fortified settlements) in key locations. King Alfred had already created a network of burhs in Wessex and this undoubtedly served his daughter and son-in-law as a template. At Gloucester, a former Roman city on the River Severn, the new burh constructed by Æthelflæd and Æthelred became their ‘capital’. Here they built their principal church, dedicated to St Peter, intending that it would eventually serve as their mausoleum.

Alfred’s ultimate goal was to bring all the English together as a unified nation in a single kingdom ruled by the royal dynasty of Wessex. Turning this vision into political reality was no small challenge, even for a man of his ability. As a starting-point, it required the liberation of all those areas that had been seized and occupied by the Great Heathen Army, such as East Anglia, eastern Mercia and much of Northumbria. When Alfred died in 899, his hope of creating a ‘kingdom of the English’ still remained unfulfilled. The lands under Viking control – collectively known as the Danelaw among today’s historians – emerged into the tenth century largely intact, with forces still capable of launching destructive raids. Yet Alfred’s vision did not die with him. It was taken up by his son and successor Edward, himself an experienced warlord who had already fought many campaigns. A bond of comradeship between Edward and Æthelred, sealed by their kinship as brothers-in-law, ensured that the close alliance between Wessex and Mercia continued. The human embodiment of this alliance was Æthelflæd, yet she was no passive link in the bond between her husband and brother. To a large extent she was Æthelred’s co-ruler, playing an active role in the business of government and undertaking burh-building projects of her own.

Chester’s medieval walls, with a surviving section of Roman stonework in the foreground. (© B. Keeling)

In 907, Æthelflæd took upon herself the task of rebuilding and refortifying the old Roman city of Chester, a huge site that had fallen into dereliction. It lay in the north-west corner of Mercia, far from her husband’s core territory in the Severn Valley. Together with its dependant districts it was now added to Æthelred’s realm, having first been cleared of Viking marauders and other rogue elements. Three years later, Æthelflæd ordered another burh to be constructed, at a place called Bremesbyrig which unfortunately cannot now be identified. At both Chester and Bremesbyrig she is likely to have directed military campaigns to secure the surrounding lands.

Æthelred died in 911, apparently succumbing to an illness that had left him incapacitated for long periods. Patterns of succession in the early medieval period or ‘Dark Ages’ were based on patriarchal customs, with the reins of power normally passing from one man to another. In this instance, the Mercians recognised Æthelflæd as their new ruler. This was a highly unusual step, for female rulership in those days was so rare as to be almost unheard-of. Æthelflæd’s elevation to power was a clear testament to the leadership qualities she had displayed throughout her marriage. With her husband gone, his people were in no doubt that she was the right person to succeed him. Just as they had referred to Æthelred as myrcna hlaford, so now they bestowed a female version of this title upon his widow, calling her myrcna hlæfdige, ‘The Lady of the Mercians’ .

Æthelflæd proved herself to be more than adequate for the role. She stands out as one of the great rulers of the Viking Age, one who was equally adept at governing her subjects as in leading them to war. A contemporary chronicle known as the Mercian Register preserves a summary of her achievements, recording many of her burh-building ventures and military campaigns. From it we learn that she reconquered large swathes of territory that had once belonged to Mercia’s kings. Each new burh that she ordered to be built represented the culmination of a successful period of warfare through which she expanded her domain. In the north, she pushed her frontier to the ancient Mercian boundary on the River Mersey, placing a burh at Runcorn on the southern bank. In the west, her border with the Britons of Wales was strengthened by the construction of at least one new burh. When, in 916, an English bishop was murdered by Welsh assailants, Æthelflæd launched a swift and deadly strike across the border. Her army stormed a royal lake-dwelling or ‘crannog’ in the Welsh kingdom of Brycheiniog and captured the occupants, among them the king’s wife.

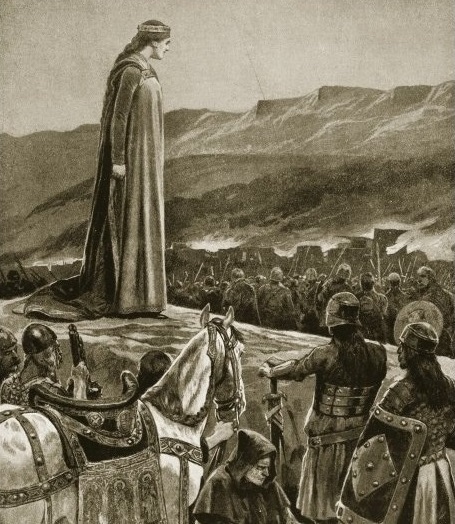

Æthelflæd supervising the assault on Brycheiniog in 916. Illustration by Richard Caton Woodville (1856-1927).

It was on her eastern frontier, however, that Æthelflæd recorded her greatest military successes. This borderland formed part of a long boundary separating English-held territory in the south and west from the Danelaw in the east and north. Both Æthelflæd and her brother Edward undertook successful campaigns to push the boundary further and further back, recapturing swathes of territory that had lain under Viking control for more than a generation. Leading the men of Wessex, Edward drove hard against the occupying forces in south-east Mercia and East Anglia. His sister mounted similarly aggressive campaigns further north. In 917, she besieged and captured Derby, one of the most important Danish strongholds. This was a major victory that enhanced her reputation as a war-leader. In early 918, the Danes of Leicester surrendered to her without a fight, presumably not fancying their chances on the battlefield. Soon afterwards, the large and powerful Anglo-Danish kingdom of Northumbria approached her with a promise of allegiance. Sadly, before she could accept the offer, she died at the ancient Mercian settlement of Tamworth, a place that she herself had rescued from dereliction by making it one of her new burhs.

Modern depictions of Æthelflæd in sculpture, paint and other artistic media often show her in martial guise, with sword or helm or other military gear. There is no doubt that her victories in battle and her strategic burh-building are indeed worthy of commemoration. Yet she achieved so much more, in fields such as administration and religion, and also in what we might call ‘town planning’. Some of her burhs were not just fortresses but embryonic urban settlements that later became important medieval and modern towns. Their design, from the shape of their perimeter defences to the present-day layout of streets, can be credited directly to Æthelflæd. On the religious front, she actively promoted the cults of a number of Anglo-Saxon saints who had strong Mercian connections. Among these were the hermit Beorhthelm (also known as Bertelin) and the royal nun Werburgh, both associated with Staffordshire. Closest to her heart was St Oswald, a seventh-century king of Northumbria martyred in battle by pagan Mercians and subsequently venerated by their Christian descendants. In 909, Æthelflæd and her husband orchestrated the recovery of Oswald’s bones from a shrine at Bardney in the Danelaw. Formerly an important monastery in north-east Mercia, Bardney had been plundered by Vikings and was no longer a safe place for holy relics. An expedition was mounted to retrieve Oswald’s remains, bringing them westward to Gloucester so that they could be reinterred in a new shrine at St Peter’s church. Founded by Æthelred and Æthelflæd some years earlier, St Peter’s was eventually re-dedicated as St Oswald’s Priory. The site is still marked by medieval ruins but nothing is left of the crypt that once housed the martyr’s shrine and the tombs of Æthelflæd and her husband.

St Oswald’s Priory, Gloucester. (© B. Keeling)

The epilogue to Æthelflæd’s story comes in the immediate aftermath of her death in June 918. What happened next was unprecedented, for her successor was not a new Lord of the Mercians but another Lady – her own daughter, whose name was Ælfwynn. As an only child, Ælfwynn had no brothers who could have taken the mantle of power. Nor did she have a husband, despite being an adult woman of about thirty. Yet her people accepted her as their new ruler, hoping perhaps that this second myrcna hlæfdige would follow in the footsteps of her renowned mother. They must have believed that Ælfwynn was capable of meeting the challenge. Indeed, Æthelflæd herself must have held the same belief, for the succession had surely been planned by her. It is a pity, then, that Ælfwynn was deprived of any real chance to prove her mettle. After ruling for only a few months she was deposed by her uncle, King Edward of Wessex, who sent her to his own realm in the south. Nothing more is known of her. It is possible that she was forced to become a nun, spending the rest of her life in obscurity in a West Saxon religious house. In such an environment her former status could be conveniently forgotten.

Sculpture of Æthelflæd and her nephew Athelstan at Tamworth. (© B. Keeling)

Turning our attention back to Æthelflæd, we might ask why her achievements are not more widely acknowledged and celebrated. Despite playing a significant role in ending the Viking occupation of England she remains largely unknown among the general population today. Many more people have heard of her father, King Alfred the Great, and probably know at least some part of his story. To him the beginnings of England are often attributed, even though he never actually became a king of all the English. That label belongs rather to his grandson, Athelstan, who by c. 930 ruled an area similar to present-day England. Many historians believe that Athelstan learned the craft of kingship from Æthelflæd, his aunt, during a period when he lived in Mercia as her foster-son. He could hardly have found a better mentor. In high-level tasks such as generalship, diplomacy and governance, few of Æthelflæd’s male contemporaries among the kings and warlords of tenth-century Britain could claim to be her equal. She was, beyond all doubt, a truly exceptional individual. Granting her a place of honour alongside her father as one of the key figures in English history is surely long overdue.

Æthelflæd: the Lady of the Mercians.

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA.

At the end of the ninth century AD, a large part of what is now England was controlled by the Vikings – heathen warriors from Scandinavia who had been attacking the British Isles for more than a hundred years. Alfred the Great, king of Wessex, was determined to regain the conquered lands but his death in 899 meant that the task passed to his son Edward. In the early 900s, Edward led a great fightback against the Viking armies. He was assisted by the English rulers of Mercia: Lord AEthelred and his wife AEthelflaed (Edward’s sister).

After her husband’s death, AEthelflaed ruled Mercia on her own, leading the army to war and working with her brother to achieve their father’s aims. Known to history as the Lady of the Mercians, she earned a reputation as a competent general and was feared by her enemies. She helped to save England from the Vikings and is one of the most famous women of the Dark Ages. This book, published 1100 years after her death, tells her remarkable story.

For more information about this book click here.

About the author

Tim Clarkson is a historian and author who writes about the early medieval period. His latest book Æthelflæd: the Lady of the Mercians was published by John Donald in June 2018. His other books, including Columba (2012) and Scotland’s Merlin (2016), are listed at his blog ‘Senchus’ . He can be found on Twitter as @EarlyScotland.

Books by Tim Clarkson

The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels & Vikings.

The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels & Vikings.

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA.

During the first millennium AD the most northerly part of Britain evolved into the country known today as Scotland. The transition was a long process of social and political change driven by the ambitions of powerful warlords. At first these men were tribal chiefs, Roman generals or rulers of small kingdoms. Later, after the Romans departed, the initiative was seized by dynamic warrior-kings who campaigned far beyond their own borders. Armies of Picts, Scots, Vikings, Britons and Anglo-Saxons fought each other for supremacy. From Lothian to Orkney, from Fife to the Isle of Skye, fierce battles were won and lost. By AD 1000 the political situation had changed for ever. Led by a dynasty of Gaelic-speaking kings the Picts and Scots began to forge a single, unified nation which transcended past enmities. In this book the remarkable story of how ancient North Britain became the medieval kingdom of Scotland is told.

‘an approachable introduction to the written sources of early medieval Scotland and the constantly changing kingships and allegiances of the period’ – Elizabeth Pierce (Scottish Archaeological Journal, 2013)

For more information about this book click here.

The Picts: a History .

The Picts: a History .

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA

The Picts were an ancient nation who ruled most of northern and eastern Scotland during the Dark Ages. Despite their historicalimportance, they remain shrouded in myth and misconception. Absorbed by the kingdom of the Scots in the ninth century, they lost their unique identity, their language and their vibrant artistic culture. Amongst their few surviving traces are standing stones decorated with incredible skill and covered with enigmatic symbols – vivid memorials of a powerful and gifted people who bequeathed no chronicles to tell their story, no sagas to describe the deed of their kings and heroes. In this book Tim Clarkson pieces together the evidence to tell the story of this mysterious people from their emergence in Roman times to their eventual disappearance.

‘a valuable resource’ – Jessie Denholm (Scottish Genealogist, September 2011)

For more information about this book click here.

The Men of the North: the Britons of Southern Scotland.

The Men of the North: the Britons of Southern Scotland.

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA

The North Britons are the least-known among the inhabitants of early medieval Scotland. Like the Picts and Vikings they played an important role in the shaping of Scottish history during the first millennium AD but their part is often neglected or ignored. This book aims to redress the balance by tracing the history of this native Celtic people through the troubled centuries from the departure of the Romans to the arrival of the Normans. The fortunes of Strathclyde, the last-surviving kingdom of the North Britons, are studied from its emergence at Dumbarton in the fifth century to its eventual demise in the eleventh. Other kingdoms, such as the Edinburgh-based realm of Gododdin and the mysterious Rheged, are examined alongside fragments of heroic poetry celebrating the valour of their warriors. Behind the recurrent themes of warfare and political rivalry runs a parallel thread dealing with the growth of Christianity and the influence of the Church in the affairs of kings. Important ecclesiastical figures such as Ninian of Whithorn and Kentigern of Glasgow are discussed, partly in the hope of unearthing their true identities among a tangled web of sources. The closing chapters of the book look at how and why the North Britons lost their distinct identity to join their old enemies the Picts as one of Scotland’s vanished nations.

‘….. a textbook and a very useful one, addressing a real gap in the market.’ Martin Carver (Antiquity, December 2011)

‘….. well-written and extensively researched … a valuable reference work for a complicated period.’ David Devereux (Transactions of the Dumfriesshire & Galloway Natural History & Antiquarian Society, 2011)

‘….. impressive breadth of coverage and clarity of expression.’ Philip Dunshea (The Historian, Summer 2012)

For more information about this book click here.

Columba.

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA

Who was Saint Columba? How did this Irish aristocrat become the most important figure in early Scottish Christianity? In seeking answers to these questions this book examines the different roles played by the saint in life and death, tracing his career in Ireland and Scotland before looking at the development of his cult in later times. Here we encounter not only Columba the abbot and missionary but also Columba the politician and peacemaker. We see him at the centre of a major controversy which led to his excommunication by an Irish synod. We follow him then to Scotland, to Iona, where he founded his principal monastery. It was from this small Hebridean isle that he undertook missionary work among the Picts and had dealings with powerful warrior-kings. It was from Iona, too, that his cult was vigorously promoted after his death in 597, most famously by Abbot Adomnan, whose writings provide our main source of information on Columba’s career. The final chapters of the book look at the evolution of the cult of Columba from the seventh century onwards, examining the important roles played by famous figures such as Cinaed mac Ailpin, before ending with a study of the image of the saint in modern Scotland.

‘…He can take an academic subject and turn it into a thoroughly enjoyable high street book. ‘ Amazon review.

For more information about this book click here.

Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age.

Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age.

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA.

This book traces the history of relations between the kingdom of Strathclyde and Anglo-Saxon England in the Viking period of the ninth to eleventh centuries AD. It puts the spotlight on the North Britons or ‘Cumbrians’, an ancient people whose kings ruled from a power-base at Govan on the outskirts of present-day Glasgow. In the tenth century, these kings extended their rule southward from Clydesdale to the southern shore of the Solway Firth, bringing their language and culture to a region that had been in English hands for more than two hundred years. They played a key role in many of the great political events of the time, whether leading their armies in battle or forging treaties to preserve a fragile peace. Their extensive realm, which was also known as ‘Cumbria’, was eventually conquered by the Scots, but is still remembered today in the name of an English county. How this county acquired the name of a long-vanished kingdom centred on the River Clyde is one of the topics covered in this book. It is part of a wider history that forms an important chapter in the story of how England and Scotland emerged from the early medieval period or ‘Dark Ages’ as the countries we know today.

‘Ruled from Govan, the ancient kingdom of Strathclyde stretched from Clydesdale to the Solway Firth. This book is the first to shed light on it and its ruling dynasties. A must for all interested in medieval history.’ (Scots Magazine, April 2015)

For more information about this book click here.

Scotland’s Merlin: a Medieval Legend and its Dark Age Origins.

Available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA.

Who was Merlin? Is the famous wizard of Arthurian legend based on a real person? In this book, Merlin’s origins are traced back to the story of Lailoken, a mysterious ‘wild man’ who is said to have lived in the Scottish Lowlands in the sixth century AD. The book considers the question of whether Lailoken belongs to myth or reality. It looks at the historical background of his story and discusses key characters such as Saint Kentigern of Glasgow and King Rhydderch of Dumbarton, as well as important events such as the Battle of Arfderydd. Lailoken’s reappearance in medieval Welsh literature as the fabled prophet Myrddin is also examined. Myrddin himself was eventually transformed into Merlin the wizard, King Arthur’s friend and mentor.

This is the Merlin we recognise today, not only in art and literature but also on screen. His earlier forms are less familiar, more remote, but can still be found among the lore and legend of the Dark Ages. Behind them we catch fleeting glimpses of an original figure who perhaps really did exist: a solitary fugitive, tormented by his experience of war, who roamed the hills and forests of southern Scotland long ago.

‘This is not the first time that a Scottish-based Merlin has been proposed, but Tim’s in-depth knowledge of early medieval Britain, in particular the kings, cultures and settlements of Strathclyde and northern England, means that he is better placed than most to tease out the fine strands of truth from a dauntingly tangled ball of threads.’ Jo Woolf (The Hazel Tree)

For more information about this book click here.

Tell me a story!

If you are a writer, artist or photographer…If you have a poem, story or memoirs to share… If you have a book to promote, a character to introduce, an exhibition or event to publicise… If you have advice for writers, artists or bloggers…

If you would like to be my guest, please read the guidelines and get in touch!

A great bit of history I knew nothing about.

LikeLike

She is such an important figure in English history. Æthelflæd kept cropping up in our research a few years ago…and we could not visit Chester without learning something of her story 🙂

LikeLike

Fantastic post on an extraordinary woman. I have read a number of books about that period and find it fascinating and an exciting time in our history. Thanks Sue for hosting and Tim for such a clear and interesting post.

LikeLike

I ws very glad to have Tim come over, Sally.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Smorgasbord Blogger Daily – Monday 13th August 2018 – Sue Vincent – Æthelflæd, Jennie Fitzkee – Milly’s Legacy, Learning from Dogs – #Dog #Flu Alert | Smorgasbord – Variety is the spice of life

Thanks. Sally. xx

LikeLike

Wow! Such a fascinating history dating back through the ages with empowering women. 🙂 ❤

LikeLike

She was a truly remarkable woman 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOVED this post. How interesting. The Vikings, (a TV show here in America) actually covered a bit of this history between the Vikings and King Alfred. Although, I am sure it was Hollywoodized. Great information, Sue and Tim Clarkson. ❤

LikeLike

I am very grateful to Tim for sharing a little of her story here, Colleen. ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed this, Sue. My house flooring remodel is almost over and I can look at your wonderful opportunities on your blog. ❤️

LikeLike

That would be great, Colleen ❤

LikeLike

Thank you Tim ans Sue for a bit of insight into this steadfast woman. 🙂

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person