Image: Pixabay

What can a fiction writer bring to a world with broken wings? For sure, a world like this one is full of fragmented people–fodder for a writer. And just as sure, a writer will translate human brokenness through his or her own lens. So what is my lens?

Here’s a little about why I write as I do.

For some writers, fiction is an author’s attempt to open a little window on the meaning of human life itself. Some fiction writers perceive people as good because God made them to be like Him. I am one of them. I also recognize free will. We can choose not to be like Him, and even choose not to believe in Him. But the job of a writer who sees people as coming from God, is to translate His goodness in some concrete form for her readers; and that is a difficult job in our world today because many don’t believe in a Creator, and others don’t see our world as good. So what is such a writer to do?

First, I believe this sort of writer will have strong emotion about current events where goodness is not. The murder of children. Debilitating disease. Greed. Arrogance. Sadistic, sexual perversion. Dishonesty. Meanness, and on and on–just check ‘I choose not to follow” on each of The Ten Commandments. So, the paradoxical question for a writer like myself becomes, “Can interior goodness be found when exterior goodness is not apparent?”

My lens says, “Yes!” Our Creator is powerful enough to draw out goodness from atrocities that emanate because of the misuse of human free will. In this writer’s imagination, there is a link between the Divinity of God (the supernatural world) with the natural world. The task becomes that of interlocking the two. Representations are created, and specific truths about God’s presence in our world appear in the writer’s mind. She translates it in her settings, characters, and dilemmas. And what she translates is a tenet called grace, both Sanctifying Grace and Actual Grace. Sanctifying Grace, inherited from the God who made us, lives in the soul and stays in the soul. By contrast, Actual grace doesn’t live in the soul; rather, throughout a lifetime, it acts in the soul as divine pushes from God toward His goodness. But those pushes require cooperation. The translating writer understands that a person must accept grace by his own free will; and grace, like love, is sometimes prickly.

A writer who translates grace in a world on edge must first have a well-written story. Then she must see a double beginning and ending in everything, and I mean everything, including the awful, current events mentioned above. Along with this, she realizes that knowing reasons why is a human characteristic. She perceives a cause, and an effect that creates another cause, and effect, and so on. Stories are discovered in her imagination and brought to light by a very intimate flashlight, one that shines a light on the many causes and effects of free will, and on the causes and effects of grace; both working, and often conflicting, in the same human soul.

So, I write books that center around the many misguided bandages my characters put on their inevitable broken wings, all those wounds that life churns out.

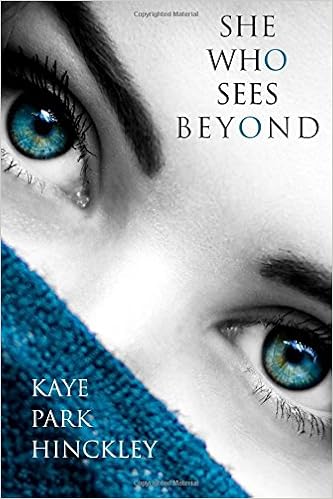

Here’s the first chapter of my novel, “She Who Sees Beyond.”

1

AUDREY

Purpose

Orleans Parish. August 29, 2005

This is happening to someone else—not to her! She will not be the woman in this nightmare, crouched atop a tall kitchen cabinet, forced to watch the rancid canal water rise and confront her like an ominous growling ogre. It creeps up the twelve-foot high walls. Already it is just below the clock above the stove, but it will come in higher! It will lap against her feet, her knees, and upward in this certain dream—this is a dream!– where across from her a man hunches, squeezed between two wide-planked shelves, his brown hair disheveled as a waking child’s, his eyes as blue and lovely as the farthermost point on the horizon. Their four year-old boy wrapped in his arms, shielded as something sacred.

The eyes of the woman—she is an artist, a potter–meet the eyes of the man, a physician. Their gaze inter-locks joys and sorrows shared in the past, then turn to the child meant to be their future. The odorous, brown water will take all that from her. She knows this, and can do nothing to stop it.

Her boy cries. The man, his father, consoles him with the compassionate touch of a healer. The woman, his mother, sings to him from across the room. You are my sunshine, my only sunshine. The child’s favorite song.

The water continues to rise.

The father turns a flashlight to the watery-faced clock. Five o’clock in the morning. The sound of wind whirs like a thousand locomotives. The mother’s song can barely be heard. The boy’s crying is muted. The father calls to her above the noise, I love you. She mouths the same. The water slaps at their lips and mixes with tears. Then they are swallowed.

In the nightmare, they float together, within the water, within time, between beginnings and endings—until outside the kitchen window unrestrained debris charges forward like wicked dragons in a frightening fairy tale.

A catapulted pole of metal shatters the window as if hurtled by a purposeful fist, striking the woman painfully on the left side of her head. A violent sucking, a tunnel of dirty red draws her through the broken glass into the water’s immenseness where there is no floor, no ceiling, nothing to hold on to, only a strong, merciful swirl beneath her feet to force her upward.

The woman rises above the city street, now a raging sea. Overhead are flashing lights and spinning propellers and radio-like calls. The swaying water splashes against her, sounds of encouragement: Stay afloat. Stay afloat.

Ropes descend from a cradle in the sky. She grabs them, imagines a lullaby: Rock a bye baby, in the tree tops. When the wind blows the cradle will rock. She cries out for her angel boy.

Then darkness. Then nothing.

When light returns, the woman shivers in a helicopter, her palms are bloodied by the gnawing of ropes, and there is a scraping inside her chest as if her heart is being shredded.

The nightmare is real. It is happening to her!

Please. My son and my husband are still down there.

Yes, there are so many. We can’t reach them all. Is there some place we can take you?

Three nights later, the woman tosses and turns in the borrowed bed of a New Orleans convent, battling the image in her mind of a nearby canal, of its disintegrating bank tearing toward the Gulf of Mexico. The image will not relent, will not release her. And so, she sees the angry soup of mud carrying the cobalt-colored body of her husband, his arms are cradled around nothing now. Her heart decomposes. Her breath becomes nothing. But the empty arms still flail in her mind like the wings of a storm-battered bird. Out of the liquid mud, her name is called, again and again, until she leaves the borrowed bed and hurries from the convent. Four blocks to the collapsing canal.

Two recovery officials in protective suits are bagging a body. His body. She pushes them away and kneels beside him, her fingers moving over his unyielding lips. Our child; where is our child?

Only an echo of memory answers her. Like a blurred radio station, it plays and replays their first meeting, their first kiss, the birth of their son, their happiness. And then his betrayal, her wrath, her forgiveness. All unchangeable now.

You should go home. We have a morgue set up. Is there a funeral home you’d like us to call? The words are caring, but she cannot answer. From her throat comes only the hum of grief. Her husband and son, gone. A discarded childhood gift, restored. The woman’s life, in a few fast hours, transfigured.

Come with me, sweetie; I’ll walk you back to Ursuline.

On the woman’s bed, an old nun sits. She opens her arms and breathes out the smell of incense. “You will be alright, my little bird. You will come through this.”

The nun strokes the woman’s face; the same nun who once placed the child’s gifted fingers around clay spinning on a kiln. Gently, little bird. Gently now. Let it spin, let it speak to you, and you will see purpose in the clay.

“Come through this? How?” the woman asks.

“Sleep,” the nun says. “Close your eyes and ears for a time.”

The nun covers her with sheets of kindness, but the woman only hums. She does not sleep until the humming in her throat is stopped by the voice in her head. Mama. Mama. Find me!

For days, the cry is her magnet. It beckons, she follows. Dead-ends. Dead-ends. Until the voice fades and she accepts that her child will not be found.

On that day of lost hope, she stands in the flooded courtyard of the Ursuline Convent beneath the tall, white image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. All around the statue is the slosh of old debris, yet not a splash of filth adheres to the statue. And not a piece of it has been broken by the horrific wind. It is immaculate. As if newly created, it shines in unstoppable sunlight.

Dropping to her knees in the black muck, she longs for the purity of gentler times; the white linen cloth of her Baptism, the white mother-of-pearl missal of her First Communion, If only to be a child again, to unwrap every first thought and see it spiral and dance like the striped metal top her father once gave her. She was certain those thoughts came from angels, stone angels in a garden, but other angels, too–everywhere, and not one looked the same. She laughed a lot then, pointed at nothing, and played with children no one else could see. Colors amazed her. She drank them in, tasting red and orange leaves, purple dawns, and dark velvet skies that sparkled with diamonds. Into her skin, she drew the softness of a breeze. Into her ears, the symphonic twitter of birds, the lazy sloshing of the Mississippi, and the sweet sound of silence. In time, she responded to conversations not yet had, and answered questions not yet asked. Her mother called her my mystical princess. Her father put his arms around his inventive pet. And she played out her childhood in a shadow-less world where nothing was hidden, where she saw beyond seeing, and heard beyond hearing. And then, with the death of her parents, the gift withdrew from her, as if the fresh bloom of a rose had somehow tucked itself back into the bud.

Until the hurricane.

In the courtyard at Ursuline, she raises her eyes to the unblemished stone face of the unsullied statue, then widens her vision to the surrounding ruin, and makes a vow of celibacy. Not for a noble reason. Once, she put on a lacey veil and pledged herself in marriage to a man she dearly loved. Once she held a child and felt holy in his presence. Once, she had everything. Now, she has nothing. She will not love again. She is afraid of human love.

And yet, through the whisper of a wayward wind, she hears the cry of another child when there is no child near. She sees an eighteen month old baby in the attic of a specific house in the Ninth Ward. Nestled next to the child, is the dead body of an elderly woman. Another day goes by before she has courage enough to speak about it to the aged nun who doesn’t question her revelation, but sends an immediate message to a grand nephew, a New Orleans policeman. The attic is checked by the NOPD. The baby is found alive.

Soon, other voices call to the woman, each conjuring up a different face, a different body, a separate need for help. Come now. Come now. Find me! How can she not answer their sobs, or turn a blind eye to their faces?

The last is a little girl, abducted from Birmingham, Alabama and taken to New Orleans, days before the storm. Again, the police are called. Again they call the woman. Just as she visualized, they discover the five-year old buried in Orleans parish in a relative’s backyard; a beautiful child with copper-colored hair, a dirty plaid ribbon around her ponytail and a wire around her lifeless neck.

The New Orleans Picayune runs the murdered child’s picture on their front pages with the woman’s picture beside it. The headline reads: She Who Sees Beyond. The story is picked up by The Birmingham News. An interview with the head of the Alabama Division of the FBI secures more consultations from her about unsolved cases. The woman is soon sought after by the agency as one who discovers the missing.

Other questions come to her then: by phone, by letter, by desolate and broken people knocking on the convent door. Can you help me? Can you solve the murder of my child? Can you find my wife? My husband? Other interrogations do not fail to follow: Is it a gift from God? Is it Satan’s bribe? How do you do it?

She cannot answer their questions. She knows only that tragedy transformed her, reestablishing the gift she was born with, and returning her to a convent of women in seclusion. It has become her place of acceptance, a place to heal the wounds of human love, lost. Her island after the storm.

And then, Audrey Bliss is handed an island of her own.

Find and follow Kaye

Facebook Twitter Amazon Author Page Wiseblood Books

A World on the Edge Blog Website Goodreads

About the author

About the author

Kaye Park Hinckley writes southern literary fiction from a Catholic perspective. A graduate of Spring Hill College, Mobile, AL, Hinckley owned an advertising agency for twenty years before she began writing full time. Many of her stories have been published in literary magazines, such as Dappled Things, and Tuscany Press’s Anthology of Short Fiction. In 2013, the Dothan, AL native published her debut novel with Tuscany Press, A Hunger in the Heart. In July, 2014 Wiseblood Books published her short story collection, Birds of a Feather. Englewood Review of Books listed Birds of a Feather, as one of the six best fiction books of the first half of 2014. Hinckley won the 2014 Poets & Writers Maureen Egan Award, First Runner-up, for Faithful, a novel in progress. Since then, Hinckley has published four additional novels. She blogs at http://www.aworldontheedge.com.

Praise for Kaye Park Hinckley

“Kaye Hinckley writes deeply textured stories with a distinctive voice. Characters caught up in complex relationships, seeking yet often rejecting redemption.” Arthur Powers, ‘A Hero for the People’.

“A talented and sensitive Catholic writer whose complex stories are gripping, memorable, and abounding in nourishment for readers hungry for substantial Christian fiction.” The Catholic World Report.

“The reader is delighted by beautiful prose, then challenged to examine the longings of the soul. In the process he learns about faith. ” Dr. Ron O’Gorman, MD, ‘Fatal Rhythm’.

Books by Kaye Park Hinckley

Click the titles or images to go to Amazon

A New Orleans hurricane takes the life of artist Audrey Bliss’s husband, swallows any trace of their four year-old son, and dramatically changes Audrey when she suffers a head wound. She’s always been perceptive, but now she sees and hears the voices of missing people calling to be found. Soon, asked by local law enforcement to solve crimes in The Big Easy, she finds many missing people, including a girl from Birmingham, Alabama found murdered in New Orleans. Yet, she never finds her own son, and accepts he died in the hurricane. After inheriting a tiny island in the Tennessee River near Red Clay Springs, Alabama, Audrey attempts to discard her life as a seer and takes up residence in the old house to concentrate on her art. But when an unidentified boy is found dead on a pyre, her gift of seeing will not let go.

Beginning in eighteenth century Ireland and then set against the background of a burgeoning America, The Wind That Shakes the Corn tells the story of the feistiness of Scots Irish immigrants, and the heart-held faith and courage that led their struggle toward individualism in America. Nell Dugan’s hatred, but also her love and determination, spotlights the Irish, both Protestant and Catholic, who bring to Revolutionary America age-old grudges against longtime English rule.

On Nell’s wedding night in Ireland, English soldiers abduct her from the arms of her Scottish Lord and throw her on a ship, slave-fodder for a West Indies sugar plantation. But Nell uses her beauty and cunning to seduce the plantation owner’s son who sneaks her away to pre-revolutionary Philadelphia where she agrees to marry him, keeping secret her marriage to the Scottish lord she truly loves, and swearing to pay back the English not only for her own kidnapping but also for her mother’s hanging two decades earlier.

A story of love, hate, revenge, and the ever-hovering choice to forgive.

In 1955 Florida, a boy struggles with the effects of World War II on his family. His beloved, shell-shocked, father is a decorated hero who stages continual games of war to train his son; his bigoted, alcoholic mother blames the misfortune in her marriage on the soldier whose life her husband saved; and his manipulative grandfather stirs up trouble between mother and son, until the boy must fight a personal war just to survive.

When the boy’s father is suspiciously shot and killed, his grandfather accuses his daughter-in-law, and a bitter estrangement between the boy and his mother is set in motion, tempered only by the family gardener and a neighbor girl with family problems of her own. A story, ultimately, of hope and love. How we find it and thrive in even the darkest circumstances.

Other books by Kaye Park Hinckley

Tell me a story…

If you are a writer, artist or photographer…If you have a poem, story or memoirs to share… If you have a book to promote, a character to introduce, an exhibition or event to publicise… If you have advice for writers, artists or bloggers…

If you would like to be my guest, please read the guidelines and get in touch!

![A Hunger In The Heart by [Hinckley, Kaye Park]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51KK1xi9YpL.jpg)

Pingback: Guest Author: Kaye Park Hinckley – The Militant Negro™

Thank you for sharing Kaye’s post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fiction from a catholic perspective sounds very interesting. Thank you for posting Sue!

Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Michael 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Die Erste Eslarner Zeitung – Aus und über Eslarn, sowie die bayerisch-tschechische Region!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Much gratitude to you, Sue, for this post! I am so fortunate to have been included on your delightful blog. You obviously care much about writing and words, so this is for you:

“Always the seer is a sayer.

Somehow his dream is told:

Somehow he publishes it with solemn joy:

Sometimes with pencil on canvas:

Sometimes with chisel on stone;

Sometimes in towers and aisles of granite,

His soul’s worship is builded;

Sometimes in anthems of indefinite music;

But clearest and most permanent,

In words.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Selected Essays

LikeLike

Thank you for being here today, Kaye! And huge congratulations on your award for The Wind That Shakes the Corn!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on DSM Publications and commented:

Meet guest author Kaye Park Hinckley from this post on Sue Vincent’s blog.

LikeLike

Thanks, Don.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person